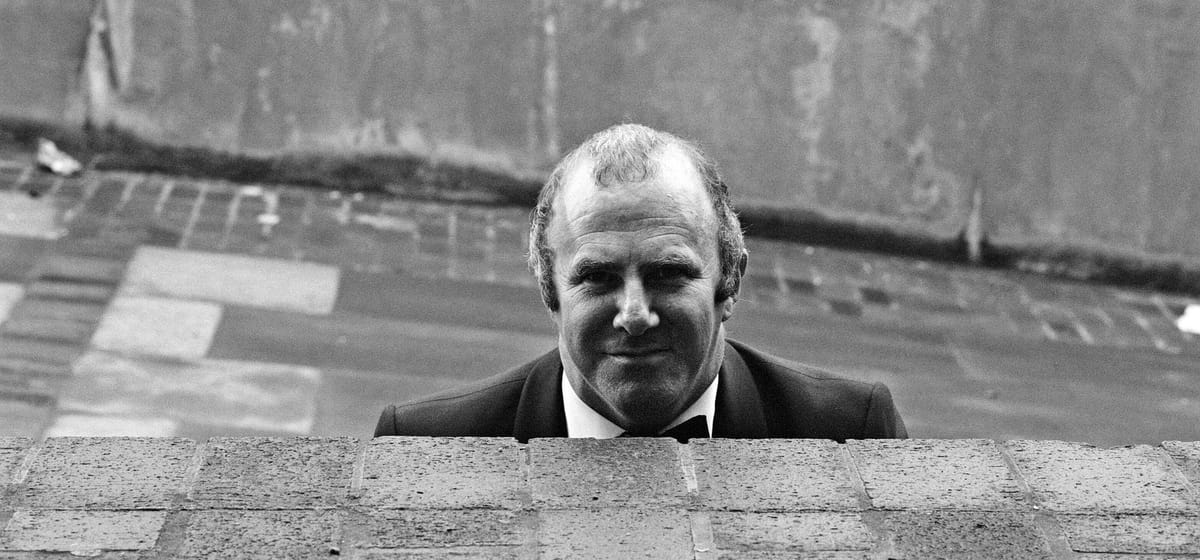

Musical Clive James

Clive James was simply unique

I have read and listened to the last half of Clive James' autobiography several times. Every time I reach a different conclusion about why I do this. When I was ten or twelve, he was the face of every new year on television. I cared little for any new year because everyone who knows, knows that September is the start of every year, not January. But Clive made the end of December important. He was so funny, he was worth staying up for.

It would be easy, lazy and wrong to say that it's impossible to explain why someone is funny. Clive James had the perfect job at the perfect moment, not only in terms of his life, but in the life of television itself. We no longer have these end of the year shows as a concept, which makes the challenge all the greater.

He consciously became a TV personality at a time when TV was the prime entertainment medium. With only four channels, and nearly all of them in colour, half the country watched BBC-1 and the other half watched ITV. Clive was on both of them, and (seldom) at the same time.

Clive was a poet and novelist first and foremost, though he never made any money at either. Even he noticed that he would have to do something with broader appeal if he was ever to progress beyond being the 'oldest student in Cambridge' as one colleague once badged him. His newspaper column about the week's TV was so funny it became part of the NHS accident statistics in the 1980s. Even cynical professional writers and critics fell about helpless on the nearest floor whenever they opened to Clive's page.

Clive was funny, first and foremost, because he was an outsider. He loved England, and Cambridge, with an ardour that only an Australian can. His fresh eyes made him aware that he had arrived somewhere special and important. His boyish enthusiasm for even the most mundane part of life... burnt toast, for example, and burnt toasters, for another, made him fun to be around. The TV Clive was essentially the same person as the Clive at home. There really was only one Clive James.

What Clive James spotted, and he was the first to do this on television, was that humour could tell us serious things about the world. As the photo shows he was living proof that men who are not good-looking can still be attractive. Even and especially on TV, his eyes sunk back so far into his face as to be beyond the reach of any type of human lighting, and even beyond the reach of the sun itself. So you never knew what his eyes were doing, except that it could be surmised. They were always darting from side to side, tearing up with merriment.

And because Clive wrote poetry, he had a good eye for the right poets. He was a lifelong fan of Hull's very own Philip Larkin. I only knew this after his death in 2019, and I was pleased. As you know, I am from Hull, and I too am a lifelong fan of Larkin. Clive loved Larkin so much that he compiled a book of his Larkin articles called Somewhere Becoming Rain. It is Hull on both covers. The title is the last line from one of Larkin's most famous poems, in perhaps his most famous collection, The Whitsun Weddings, a poem I studied at school while I laughed myself half to death over Clive's TV postcards and interviews.

Incredibly, Clive was a big Formula One fan at a time when nobody watched F1 and it was rarely on TV. I knew this because he voiced the annual video highlights package sometimes. He became a friend of Bernie Ecclestone, a man once rumoured to have been the getaway driver for the Great Train Robbery. Yes, Clive was that famous in the 1980s, and in the 1990s too.

TV gave Clive the money to live on, yes, but it gave him much more than that. When the company he formed with Richard Drewett, Watchmaker Productions, was sold on, he became rich enough to do what he had always wanted to do. He cycled home, locked the door, and wrote a poem.

Every few months, and this was after Clive sold his Barbican flat to live in a high-ceilinged loft on the south side of the Thames, a young journalist would knock on the door. These were the profile writers, and they were aware of Clive's career in the same way that I am aware of the career of Charles Dickens. They had heard rumours and tall tales and wanted to know if they were true. But more than that, they wanted to know the answer to life, the universe and everything.

Clive ends his autobiography with a paragraph about luck, and in this paragraph he shares his answer to the meaning of life or, at least, his life. Many of the celebrities he interviewed, and some of the ones he became friends with, including Princess Diana, were lucky. They worked hard, sure, but they had been lucky at the right time and became internationally known.

What most of them had in common, and the reason almost none of them were happy, is that they had not been clever enough to know how lucky they really were. Most of them thought they were geniuses, and it showed. What it showed was that they were all just hard-working lucky people. The difference between those people and Clive James was that he recognised his luck while it was unfolding.

I have always known how lucky I have been, and right from the start. I had a family full of teachers which led me, one day when I was terminally bored, not to kick a ball but to write a story. I had been born in Hull, a place so dull that anyone with enough sense charted their escape as soon as they could think. Luck had forced me to write a story and to plan an escape, and I have done little else since.

It was luck that helped me to choose a different path from being a novelist. I had no issue with being poor, which is what it would have taken, to follow that dream. What I had an issue with was worry. I was a born worrier and I was not prepared to worry about how I would pay my bills. So I did the decent thing. I learned how to code, to program computers, and I did that for over ten years in London.

It turned out that programming computers is not all that different from programming humans, which is what the arts really are about. The funny part is that programming computers is far harder and better paid.

When I turned my back on computers it was to become a computer trainer, someone who showed others the dark arts. I had finally become, and by sheer fluke (friend of a friend of a friend) a professional communicator for the first time. I have never really stopped doing that, and it bought me time to write.

To my surprise, having a baby bought me even more time. I was suddenly awake for twenty hours out of any day or night. I wrote a novel for her while she was too young to read, and one day she read it. Well, the first chapter anyway. I had written a book for ten year-old me and I had failed to realise that today's ten year-olds are into different things.

Every book, every article, every sentence, brought me to a higher place. I had become, and totally by accident, a pretty decent writer. My only problem was that I didn't have a topic.

Noticing a lucky break is not as easy as it seems, but I am pleased to say I noticed my 2025 lucky break at the exact moment it happened. I was so convinced of my luck that I showed the text message to two friends. It was Tuesday, 29th April, and we were all travelling south on a train home from Manchester. I had received a text from America.

The text promised something I had not until then received: it promised a glance behind the curtains of the music business. I was being invited to listen to music that had not been released, some of which has still not been released, and I was being invited to write about it. This might not sound like much to you but what it meant to me was this: my writing had been noticed by someone three thousand miles away, and she was asking me to write even more of it.

As I knew it would, the text led to more people asking me to write about their unreleased tracks. The more it happened, the more it felt pre-ordained, inevitable. It gave me the courage to write a proposal for a book on music. The proposal went nowhere so I wrote another one, which also went nowhere. But the second proposal led to a different invitation: would I write about a single band perhaps and if so, which band would it be?

The ink had barely dried on the email before I fired back my reply: has anyone covered Fleetwood Mac yet? They had not, and so it was my turn. And more than that, I knew I could not do the job properly in a single book. So one book quickly became two, and I settle down this weekend to seriously plan it out. It needs to arrive in 2027 to mark 60 years of Fleetwood Mac, which means I need to get it finished by next September. And by it, I of course mean them.

People say you make your own luck, but those people have only half the information. A golfer, long ago deceased, once said that the more he practiced, the luckier he got. That is closer to the truth but still falls short. Although it is true that the more words I write, the more interesting they become, at least to me, the source of luck does not come from within.

Luck comes from getting noticed. If you write words that nobody else wants to read, you will never get a lucky break. Luck comes from without. The hard yards are carried out within, but luck is something that comes to you from somewhere else, and most commonly, from someone else. I have always spotted my luck in whatever form it took, and was willing to chase the dream wherever the chase led.

Having long ago learned that there is nothing more unfulfilling in life than having your dreams come true, I change my dreams every few years. Now I have a topic, and I have the skills, and I have luck on my side. Now is the time. LFG.

This article has been a very long way to say that episode two of our chat is now available on Tennessee Vibes and on Spotify. Both links are below.